Portraits

Portrait of an Institution

Intimate Portrait Human Archaeology Portrait of a Concept Portrait of a Relationship Portrait of a Developmental Stage Portrait of a Process Intimate Portrait

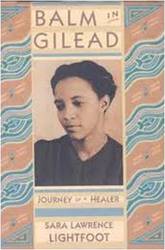

[Margaret Morgan Lawrence (1932)] For my mother, our collaboration is a psychological and spiritual journey. The journey back through time feels like a tunnel, dark, mysterious, and finally luminous. For a year and a half my mother and I met weekly to talk about her life. Until his death three-quarters of the way through this project, my father told me his story as well, bravely battling his illness to piece together a coherent narrative. The days were long. In the early morning, I would fly from Boston to New York, then drive the hour and fifteen minutes to my parents’ home thirty miles northwest of the city. At day’s end, I would retrace the miles, landing in Boston after my children were sound asleep. One night, a soft kiss on my six-year-old daughter’s brow woke her. She wiped her eyes clear and asked in a pleading voice, “Mom, why can’t you just call Nana and Papa on the phone to learn about their lives?” Before I could begin to reply, she answered her own question: “Oh, I know, you have to see their faces so you can know what they mean.” With that insight, she dropped off into a deep sleep. The interviews with my mother were all held in her office, a suite of rooms connected to her house, but separated by a garage and a workroom and by a psychological distance that makes it feel as if the office were across town from the kitchen. Over thirty years later, I can still hear my mother’s firm tone of voice, saying to us as she headed over to her office, “Do not disturb me unless it is an emergency.” Despite scraped knees, sibling battles, and injured spirits, we did not test this boundary. Margaret’s office is dominated by “the playroom,” a big open space with a larger-than-life-sized clown whose face is pocked with dart holes, a long red counter for art and clay work, a sink for water play, a punching bag, a handmade wooden cradle that fits big bodies as well as small, cabinets several feet above adult height that can become a tree house or a secret hideaway. The consultation room, where we meet for our interviews, is a smaller, more adult space full of treasures that reflect Margaret’s history and passions. Because this is where Margaret sees her adult patients, there are more typical doctor’s office furnishings: medical degrees, diplomas, an answering machine atop a small teak desk; an entire wall is covered with books and journals. As we talk, I sit in the chair used by most of my mother’s patients. It is a comfortable, simply designed Danish chair with green woven fabric, placed to face the doctor directly. Margaret Lawrence likes to see her patients. This arrangement permits no obstruction and no escape between doctor and patient. As she sits at her desk, Margaret can also look out into the woods. She calls the view “dreamy” and seems to derive nourishment from this direct connection to nature. As she listens to her patients, she watches the change of seasons: new buds, full summer lushness, reddening maples. When winter comes, she can follow the winding path of a brook several yards from the office. Margaret’s body settles into the chair; she straightens her back for comfort, clasps her hands in her alp, and fixes her eyes on me. She is ready. I feel her full attention and eagerness to proceed. She looks forward to our sessions, for the chance to sit together uninterrupted, for the excuse to focus on her own life. I turn on the tape recorder, prepare to take notes, and remind her of where we traveled during our last session. Once she gets located in time, Margaret needs little prompting. She pauses as she reflects on the many paths converging in her head. She picks one and sets forth. The story gains in feeling and intensity as she proceeds, churning up fantasies, dreams, and new detours. If I insist on a literal tale or stop her for facts, she loses her momentum. Margaret moves through time and space in her own characteristic way. Her mind is poetic and playful, not literal or analytic; she rarely follows strict chronology, rarely remembers dates but never forgets history. She speaks directly from feelings, from emotional content. Her mind puts things together that others see as disparate or unconnected. She can make patterns from stray remnants of all shapes and colors. Hers is an intelligence exquisitely suited to a psychoanalyst who must help the patient integrate fragments of history, gathering loose threads from the distant past. Margaret’s memories are not edited. Only twice in our sessions together has she censored herself. Usually Margaret does not restrain the images and feelings that seem to tumble out of her mouth “of their own free will.” She does not hold back rage or tears or laughter. More than once, Margaret exclaims softly, “This feels like a second analysis.” After every session we are exhausted—sometimes exhilarated by discovery and memories of victory, sometimes saddened by images of defeat and humiliation. We travel together across time and space, tracing Margaret’s ancestry, her parents’ marriage, her childhood and adolescence, school and college, her own marriage and early years as parent. As I travel with my mother, I am most interested in her interior journey. I listen for how she feels about the family drama, not for bare facts. I listen for how she perceives community, prejudice, illness and healing, not for an objective rendering of the sociohistorical contexts. Her narrative is enriched by hundreds of letters she has saved, by diaries, school records, fellowship applications, medical reports, and photographs. I am able to contrast her voice with her written work: published articles, essays, and books and unpublished poetry. My mother and I carefully separate our book interviews from our family talk, vigilantly marking the boundaries so that the work will keep its integrity and momentum and so that we can recapture our familiar mother daughter patterns. This is not as hard as we feared. We walk from the office to the kitchen and feel ourselves moving back into the present and back to family habits. My mother provides the cues as she spots a thirsty plant (“Maybe I’m giving it too much direct sun”) or asks about her four-year-old grandson (“How is Martin? Is he loving nursery school?”) Soon we are putting the finishing touches on dinner, back in the old groove together. My mother anticipates my visits by fixing special feasts. The veal stew, the shrimp stir-fry, are both bountiful and beautiful, and we are always hungry after our work. We make it through these days, I realize, much the way we manage our lives—living fully in the moment, concentrating completely, and providing markers that define the occasion. Dinner is ready, the table is set with a golden tablecloth and burnt-orange napkins. We sing grace, two women’s voices praising the journey.

|