Portraits

Portrait of an Institution

Intimate Portrait Human Archaeology Portrait of a Concept Portrait of a Relationship Portrait of a Developmental Stage Portrait of a Process Human Archaeology

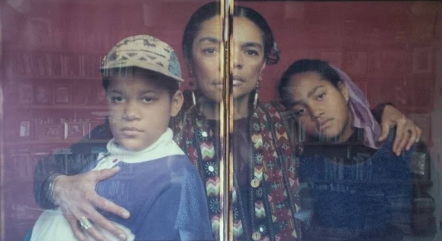

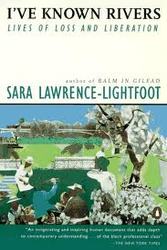

[Photographer: Dawoud Bey (1991)] The six storytellers—three men and three women—of I’ve Known Rivers speak about how they perceive and navigate the generational contrasts between their lives and those of their parents and grandparents, and about the ancestral legacies that have survived and those that have been discarded. They speak about their feelings of loss—loss of security, of community, of relationship, of rootedness, of family bonds, of heritage—even when all the external signs point to gains in education, status, income, mobility, worldview, and effectiveness. They reveal the nostalgia, ambivalence, insecurity, and guilt that often accompany ascendancy; the seemingly inevitable trade-offs between the riches of relationship and rootedness and the riches of status and station. Actually, these stories reveal the very notion of trade-offs—of giving up one good for another—to be too simply construed, too black and white (if you’ll excuse the expression). As the stories are told, we see simultaneous layers of feeling, often contradictory—feelings of security and discomfort, trauma and wholeness, movement and inertia. Many of us have known what it is to arrive where we hoped to land and to discover that we have found a perch for looking backward, for experiencing with increasing force the pull of nostalgia, the emptiness of love. I do not think these themes of yearning and loss are peculiar to middle-class blacks. (Part of my interest in writing this book reflects my wish to explore perhaps universal experiences of all kinds of people who choose to move “up and out” and away from what seemed familiar and certain in childhood.) However, I have found the experience of African-Americans intensified in this respect. Perhaps this is due, in part, to the ancestral journey of enslaved blacks, which was cruel and involuntary, which destroyed families and communities and detached us from our precious cultural roots. African Americans have been compelled to invent a hybrid new cultural/familial form under extremely brutal and harsh conditions. Perhaps this ancestral legacy of dislocation and rootlessness still haunts the contemporary journeys black Americans make from their childhood homes to some newly composed experience. In addition to these historical echoes in the black experience of today, I think that the losses that accompany privilege are felt more fully by blacks because the predominantly white worlds we enter tend to be so unwelcoming. We strive to arrive at a secure place only to discover the quicksand of subtle exclusion. We work hard to amass the credentials and signs of status even as we recognize that our status will never assure a sense of belonging, or full membership in the white world. We feel ourselves move toward the center of power even as we feel inextricably tied to the periphery; our outsider status becomes clearer as we work to claim an insider’s place. For privileged African-Americans, these contradictory experiences of insider/outsider, power/impotence, security/uncertainty are felt, I think, with particular force. But it would be inaccurate to characterize black ascendancy as defended only by a preoccupation with loss, with divided allegiances, and with profound ambivalence. These storytellers describe a journey that is also marked by hope, creativity, and purposeful design. They are resourceful, self-critical, and courageous in pursuing their dreams and in reconciling with their roots. As a matter of fact, their success is partly due to their ability to embrace and live with contradictions. The six storytellers are all in their middle years—between their early forties and mid-fifties—a developmental place from which we tend naturally to look backward and forward. They can feel the imprint of their ancestry and rehearse the values taught by their parents even as they fashion a life for their children. They tell intergenerational stories that underscore the power of ancestry—the losses and traumas revisited by each generation—and they come to realize how difficult it is to reverse historic patterns. They also tell equally potent stories of commitment and creativity, of deliberate and imaginative ways they have constructed their work and their lives. Not only do the middle years provide a wide-angle view of generational contrast, they are also a propitious moment for reflection and reinterpretation of a life story. After years of single-minded ambition, middle age can seem like a time to pause, a time for self-reflection and stocktaking, a time to re-envision the future. For these storytellers, I realized, it is also a time to take on risks. Having hit their stride, discovered their strengths, developed a craft and found their voice, they become more daring. This daring is reflected in the willingness of the six individuals to participate in the intense, demanding process required by this book. I spent close to a year in deep conversation with each one. Our conversations were intense, exhausting, exhilarating, and often painful. The storytellers in this book are working within a powerful cultural tradition. The African-American legacy of storytelling infuses these narratives and serves as a source of deep resonance between us. Our cultural and historical roots have been given expression and meaning through stories. The slave narratives, for example, were elaborate tales of survival and cunning, but they can also be read as vehicles for individual empowerment, community building, and cultural transmission. In telling the story, the narrator defined his/her full humanity. A strong and persistent African-American tradition links the process of narrative to discovering and attaining identity. A more ancient source of storytelling flows from the African continent, where stories were often embedded in tribal ritual, filled with entertainment, adventure, moral lessons, and cultural wisdom. I think of the storytellers in this volume as modern day griots, perceptive and courageous narrators of personal and cultural experience. They are working in an idiom steeped with tradition and cultural legitimacy, and, therefore, supportive of their personal revelations. Storytelling, then, is central to the way these six people make sense of, and give shape to, their lives. It helps them make the “translations” between past and present, trace their losses and gains, and rehearse preoccupations that have given purpose and direction to their journeys. Storytelling requires fluidity and facility with language, a tolerance for silence as well as a comfort with words as a creative medium for expressing (and composing) feeling and thought. The narratives are enhanced by memories that capture sight, sound, smell, and touch, along with ideas and emotions. Finally, storytelling reveals life’s journey through a dynamic reinterpretation of home, a chance to reconcile roots and destinations. As we listen to these six life stories, we hear many currents passing through many generations. Each is like a river, carrying the ancestral wisdom, soothing and cooling old wounds, and nourishing a younger generation’s thirst. These six travelers have dared to explore all the currents, all the uncertainties, knowing that in order to capture the full gifts of storytelling they will have to relive pain and risk exposure. They knew from the start that this would not be a sweet sentimental journey. It would be a rocky adventure, with its own momentum, sometimes smooth, sometimes through white water and into whirlpools. These storytellers do not travel alone. I am with them; we are on this journey together. As I listen to these extraordinary women and men tell their life stories, I play many roles. I am a mirror that reflects back their pain, their fears, and their victories. I am also the inquirer that asks the sometimes difficult questions, who searches for evidence and patterns. I am the companion on the journey, bringing my own story to the encounter, making possible an interpretive collaboration. I am the audience who listens, laughs, weeps, and applauds. I am the spider woman spinning their tales. Occasionally, I am a therapist who offers catharsis, support, and challenge, and who keeps track of emotional minefields. Most absorbing to me is the role of human archeologist who uncovers the layers of mask and inhibition in search of a more authentic representation of life experience.

|