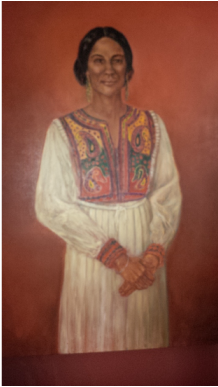

Portraitist as Subject

[Artist: Marion Cuthbert (1952)]

Many years ago an artist painted my portrait. Twice a week, for several weeks, I posed for the portrait. I would arrive early in the morning, climb the three flights to her garret studio, change into my beautifully embroidered Afghani dress and shimmering golden earrings, and stand motionless for an hour. It was difficult, wearing work trying to hold my pose, with arms hanging long and loose and hands clasped softly. At first, the stance would feel natural, then I would lose my ease. My arms would stiffen, my fingers would press each other until the red showed through my brown skin, and my jaw would grow tight. The painter would notice the slow stiffening of my body and she would offer a break, sometimes a cup of tea. But we would soon return to the task and she would encourage me to relax and think good thoughts. Finally the artist discovered the words that would produce the expression she wanted. “Think of how you would like your children to remember you,” she said earnestly. Still not thirty and not yet a mother, I found the request overly sentimental, and almost incomprehensible. I did, however, try to produce a look that conveyed goodness, nurturance, and understanding. [Artist: Susan Sirris (1971) The portrait passed through several phases and my image was transformed in front of my eyes. The transformations were all unsettling; even when the emerging image offered a prettier, more likable portrayal. With a sensitive eye, a meticulous brush, and enduring patience the artist painted me “from the inside out;” the skeleton sketched in before the bulky frame; the body contours drawn before the layers of clothing. I did not see the final product until months after completion when I quickly bought the piece fearing it would be sold, and I would be hanging in someone else’s living room. When I saw it, I was shocked, disappointed, and awed all at the same moment. I had the odd sensation that the portrait did not look like me, and yet it captured my essence. I quibbled about the eyes looking empty, the mouth being tight and severe, the expression being overly serious. I had not thought of myself as high-waisted, nor did I recognize the yellowish cast to my brown skin. The woman in the portrait looked more mature and static than I felt. “She’s thirty years my senior,” I complained to myself. I was relieved when friends saw the painting and commented on how much younger I looked in person and how the artist had not captured my vitality and spirit. Although many of the details of this representation seemed wrong, the whole was deeply familiar. She was not quite me as I saw myself, but she told me about parts of myself that I never would have noticed or admitted. More important, I had the eerie sensation that she anticipated my future and echoed my past. I could look at her and see my ancestors, and, yes, see myself as my children would see me. In these troubling features there was an ageless quality. Time moved backward and forward through this still and silent woman. I did not see Sara alone (such a singular vision forced me to complain about the details, to deny my imperfections, to flinch at the signs of aging and vulnerability), but I did see my mother Margaret, my sister Paula, my grandmothers Lettie and Mary Elizabeth—women who have had a profound influence on my life, women who have shaped my vision of myself, women who have known me “from the inside out.” And when my mother Margaret saw the portrait for the first time, she stood in the doorway of the dining room where it hung, her arms loosely hanging, her hands lightly clasped, her head slightly tilted, and her gaze maternal. A look of recognition swept over her face and tears shot to the corners of her eyes. “That’s a picture of me,” she said with wonder. And at that moment her posture and aspect made her look remarkably like the woman in the picture. The artist had caught my attempt to look maternal, a replica of the motherly eyes that had protected me all of my growing up years. This family portrait was not the first portrait done of me. It was certainly the largest and most elaborate, but I had been sketched, painted, carved, even rendered in glass before this experience—each time learning something new about myself, or about the artistic process; each time watching myself evolve with that strange combination of shock and recognition. The summer of my eighth birthday, my family was visited by a seventy year-old Black woman, a professor of sociology, an old and dear friend. A woman of warmth and dignity, she always seemed to have secret treasures hidden under her smooth exterior. On this visit, she brought charcoals and a sketch pad. Mid-afternoon, with the sun high in the sky, she asked me to sit for her in the rock garden behind our house. I chose a medium-sized boulder, perched myself upon it in an awkward, presentable pose, and tried to keep absolutely still. This suddenly static image disturbed the artist, who asked me to talk to her and to feel comfortable about moving. She could never capture me, she explained, if I became statue-like. Movement was part of my being. Her well-worn, strong, and knowing hands moved quickly and confidently across the paper. She seemed totally relaxed and unselfconscious; her fingers a smooth extension of the charcoal. Her deep calm soothed me and made me feel relaxed. But what I remember most clearly was the wonderful, glowing sensation I got from being attended to so fully. There were no distractions. I was the only one in her gaze. My image filled her eyes, and the sound of the chalk stroking the paper was palpable. The audible senses translated to tactile ones. After the warmth of this human encounter, the artistic product was almost forgettable. I do not recall whether I liked the portrait or not. I do remember feeling that there were no lines, only fuzzy impressions, and that I was rendered in motion, on the move. This fast-working artist whipped the page out of her sketch pad after less than an hour and gave it to me with one admonition: “Always remember you’re beautiful,” she said firmly. The adult and child’s experiences of being an artist’s subject were different in many ways. One quick and impressionistic, the other painstaking and laborious; one sitting on a big rock in the middle of my mother’s pansies and impatiens, the other standing on a raised platform in an artist’s studio; one with the mid-afternoon sun shining on my face interrupted by shifting tree shadows, the other with the subtle, well-placed track lights posed to offer consistent effects; one with me shifting, talking, and gesturing, and the other with me stationary and posed. But the experiences taught me some of the same lessons—that portraits capture essence: the spirit, tempo, and movement of a young girl; the history and family of the grown woman. That portraits tell you about parts of yourself about which you are unaware, or to which you haven’t attended. That portraits reflect a compelling paradox, of a moment in time and timelessness. That portraits make subjects feel “seen” in a way they have never felt seen before, fully attended to, wrapped up in an empathetic gaze. That an essential ingredient of creating a portrait is the process of human interaction. Artists must not view the subject as object, but as a person of myriad dimensions. Whether the artist feels the body stiffening and offers the woman a cup of tea, or tells the young girl that she does not have to be still like a statue, there is a recognition of the humanity and vulnerability of the subject. The artist’s gaze is discerning as it searches for the essence, relentless as it tries to move past the surface images. But in finding the underside, in piercing the cover, in discovering the unseen, the artist offers a critical and generous perspective—one that is both tough and giving. I recognize, of course, that portraits do not always capture these myriad human dimensions, nor do the encounters between artist and subject always have these empathetic, piercing qualities; but my experiences with the medium and the process influenced my work as a social observer and recorder of human encounter and experience. As a social scientist, I wanted to develop a form of inquiry that would embrace many of the descriptive, aesthetic, and experiential dimensions that I had known as the artist’s subject; that would combine science and art; that would be concerned with composition and design as well as description; that would depict motion and stopped time, history, and anticipated future. I also wanted to enter into relationships with my “subjects” that had the qualities of empathetic regard, full and critical attention, and a discerning gaze. The encounters, carefully developed, would allow me to reveal the underside, the rough edges, the dimensions that often go unrecognized by the subjects themselves. I hoped to create portraits that would inspire shock and recognition in the subjects and new understandings and insights in the viewers/readers. I am not an artist. My medium is not visual. My concern became then how I would translate the lines and shapes into written images and representations. For many years, I have been laboring over the development and refinement of “portraiture,” the term I use for a method of inquiry and documentation in the social sciences. With it, I seek to combine systematic, empirical description with aesthetic expression, blending art and science, humanistic sensibilities and scientific rigor. The portraits are designed to capture the richness, complexity, and dimensionality of human experience in social and cultural context, conveying the perspectives of the people who are negotiating those experiences. The portraits are shaped through dialogue with the portraitist and the subject, each one participating in the drawing of the image. The encounter between the two is rich with meaning and resonance and is crucial to the success and authenticity of the rendered piece. The story of portraiture begins with this central encounter experienced first as the subject of a portrait. The aesthetic, interpersonal experiences of being sketched, painted, and carved had a profound effect on my views of myself, the artists, and the medium; and convinced me of the power of the form for artist, subject, and audience. It is a story that can only be told in retrospect because it seemed to evolve as much out of intuition, autobiography, and serendipity as it did from purposeful intention.

|